Is White Chocolate really Chocolate?

- Caterina Gallo

- 3 days ago

- 15 min read

Most of what people think they know about white chocolate comes from supermarket confectionery designed for price and shelf life, from baking compounds engineered for predictability rather than flavor, and from a modern food discourse that mistakes familiarity for knowledge.

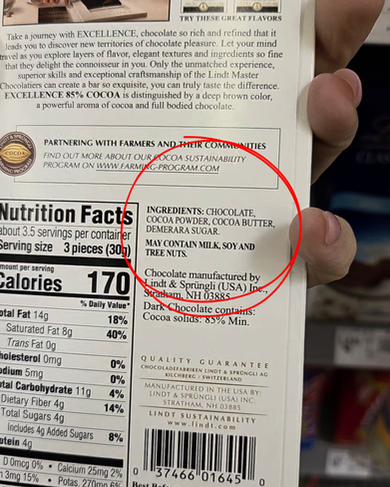

Compound coatings marketed as “white chocolate” often rely on vegetable fats such as palm kernel or coconut oil instead of cocoa butter, prioritizing stability, easy handling, and specific melting profiles helpful for decorations, enrobing, and consistent baking results.

These products dominate exposure, and exposure becomes mistaken for factuality.

Cocoa butter alternatives are not always equivalent to cocoa butter.

This confusion is reinforced by a critical distinction almost absent from public discourse between cocoa butter equivalents (CBEs) and cocoa butter substitutes (CBS).

CBEs are non-lauric plant-based fats engineered to match cocoa butter’s triglyceride composition closely, and are therefore compatible with cocoa butter crystallization. When used within regulated limits through blending or enzymatic interesterification of fats such as shea stearin, palm mid-fraction, or illipe butter, CBEs can co-crystallize with cocoa butter and preserve key structural properties, including snap, β-V polymorph formation, and melting behavior near body temperature.

Cocoa butter substitutes (CBS), by contrast, are lauric fats derived from palm kernel oil or coconut oil. At the triglyceride level, they are incompatible with cocoa butter and cannot co-crystallize with it. For this reason, they are used for low-cost confectionery, baking applications, compound chocolate, or chocolate-like products rather than real chocolate.

Their advantages are industrial: rapid melting, bloom resistance, and tolerance of temperature fluctuations. But their crystallization behavior, polymorphism, and mouthfeel differ fundamentally from those of cocoa butter.

When mixed with cocoa butter, CBS systems disrupt crystallization, leading to defects such as fat bloom. This is why they require complete replacement rather than blending.

When an alternative fat differs significantly in triglyceride composition, the resulting crystallization behavior and rheological properties of chocolate become unacceptable from a product quality standpoint, and the product is no longer equivalent to chocolate. In summary, what is rejected in most cases is not white chocolate as defined by cocoa butter, but rather compound confectionery based on incompatible fats.

Why does the idea that “white chocolate isn’t really chocolate” persist?

The problem is not simply that white chocolate is "not really chocolate because it doesn`t contain cacao solids".

The problem is that the mechanisms shaping food opinion today reward accepted dogmas without investigation, confidence without criteria, and repetition without literacy.

White chocolate has become a convenient casualty of this system: easy to dismiss, easy to mock, and easy to reduce to a punchline that generates engagement.

When the only “white chocolate” most consumers encounter is sugar-forward, made with deodorized bleached cocoa butter or replaced by "alternative" fats, the conclusion feels obvious.

But these judgments do not arise from cacao or chocolate culture. They arise from availability. White chocolate is not being evaluated; it is being inferred.

Availability is mistaken for representation.

We increasingly confuse what is widely accessible with what is representative, what is popular with what is legitimate, and what feels familiar with what is accurate.

In this environment, food knowledge is flattened into declarative takes that signal validity while avoiding responsibility.

White chocolate becomes an ideal target for this kind of framing because it violates a deeply embedded visual logic.

In modern chocolate culture, "PITCH DARK BROWN" has been trained as a proxy for seriousness.

Dark chocolate is presented as more authentic, more adult, more ethical, more worthy of attention. Milk and white chocolate are framed as childish or indulgent rather than connoisseur-grade alternatives.

These associations emerged from decades of marketing narratives that linked bitterness to health, austerity, and refinement.

Once that logic took hold, white chocolate was never judged on what it could potentially express in the right hands, only on what it lacked.

Cocoa solids are not only the definition of chocolate.

The absence of cocoa solids has become the central accusation against white chocolate.

But this accusation confuses nutritional framing with structural identity.

Cocoa solids contribute color, flavor, and polyphenolic content. Cocoa butter, however, determines chocolate’s physical structure: crystallization, snap, melting at body temperature, and the release of aroma during consumption.

Because of its chemical composition, cocoa butter exhibits a uniquely narrow melting range, approximately 32–35 °C, just below body temperature. In chocolate, this translates into rapid melting point, a characteristic cooling sensation, and efficient flavor release.

Without cocoa butter’s specific crystalline and thermal properties, a product may contain cacao-derived components, but it will not be real chocolate.

Cocoa butter is not an optional byproduct. It accounts for roughly half the weight of cacao beans, depending on genetics and origin. Removing cocoa solids does not remove cacao from the equation. It shifts which part of the bean is being used.

How white chocolate emerged and why cocoa butter was used

To understand why white chocolate entered the market, it is necessary to separate two timelines that are often conflated:

The industrial management of cocoa butter.

The later emergence of white chocolate as a confectionery product.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, cocoa butter was already a well-established industrial material long before it was framed as a flavor-bearing ingredient. Its primary value lay in its physical attributes, not in its taste. This was especially evident in pharmaceutical and medical contexts (fast-disintegrating tablets and suppositories), where cocoa butter was widely used as a base and carrier.

In the British Pharmacopoeia, cocoa butter appears as Oleum Theobromatis, classified as a suppository and ointment base. Its sharp melting point near body temperature, chemical stability, and physiological tolerance are the relevant parameters.

The same logic appears in the Deutsches Arzneibuch, where cocoa butter (Kakaobutter, Oleum Cacao) is characterized by melting range, solid fat index, and crystallization behavior. It functions as a Trägersubstanz—a carrier substance.

In the Swiss Pharmacopoeia, cocoa butter is described as a neutral lipid excipient, valued for digestibility, consistency, and tolerance.

Flavor is irrelevant in all three cases. Neutrality is the requiriment.

This matters because when large-scale chocolate manufacturing expanded in the early 20th century, cocoa butter entered food production already governed by a logic of generality.

Refinement and deodorization were not compromises. They were expectations!

Its refinement, deodorization, and standardization were not initially driven by cost or flavor suppression, but by a broader industrial culture that privileged predictability, safety, and uniform performance.

Switzerland’s role is particularly significant because it sits at a historical intersection of pharmaceutical science and industrial chocolate production. The same cocoa butter moves between these domains without being sensorially redefined.

In the 1930s, as chocolate liquor production increased, manufacturers were separating cacao solids and fat with growing efficiency.

Cocoa butter became both indispensable and, at times, abundant. It needed an outlet that aligned with existing processing infrastructure and consumer expectations.

When Nestlé introduced white chocolate with the Galak, also known as MilkyBar, the objective was not to explore cocoa butter’s aromatic potential. It was to create a shelf-stable, milk-based confection that aligned with the nutritional narratives of the time and could be integrated seamlessly into mass distribution.

White chocolate was therefore formulated to be flat, sweet, and non-challenging. It was positioned as digestible and accessible, often associated with children or gentle nourishment rather than with intensity and refinement.

White chocolate was born within a framework that viewed cocoa butter as a functional fat rather than a flavor source. It was evaluated for what it did, not for how it tasted. This shift is rarely discussed because most people have never encountered cocoa butter in a form that retains cacao origin identity.

Modern refining practices continue this legacy.

Pressed cocoa butter is commonly filtered and deodorized to achieve controlled flavor profiles.

Processes may include silica adsorption to remove impurities, optional bleaching, and steam stripping through packed columns or tray systems. Packed-column deodorization increases oil-steam contact efficiency, reducing residence time and selectively removing volatile compounds while preserving crystallization behavior.

Notably, deodorization does not necessarily damage the "structure":

Timms and Stewart (1999) report that when deodorization is conducted at lower temperatures (approximately 130–180 °C) for 10–30 minutes, no change occurs in cocoa butter’s physical properties, demonstrating that “neutral flavor” and “structural integrity” are not the same variable.

While these processes achieve uniformity and stability, they also strip aromatic compounds derived from origin, genetics, fermentation, drying, and the chocolate-making process. When the final neutralized material serves as the reference point, cocoa butter is misperceived as inherently flavorless.

The absence created by processing is projected backward onto the primary ingredient.

Conching, aroma, cocoa butter, and what white chocolate reveals

During conching, flavor development is primarily driven by moisture removal, the volatilization of undesirable compounds, and the redistribution of flavor components within the chocolate mass. This step is crucial for reducing acidity and homogenizing aroma perception. At the same time, cocoa butter at this stage plays a predominantly rheological role by coating particles, reducing friction, and enabling flow.

Aroma release during consumption, however, depends strongly on cocoa butter: its narrow melting range near body temperature governs the timing and intensity of retronasal aroma perception. These "attributes" become fully exposed in white chocolate because it lacks cocoa solids.

Legal clarity, cultural confusion

The question “Is white chocolate really chocolate?” is poorly framed, not because it is controversial, but because it ignores settled definitions.

From a legal standpoint, white chocolate is unambiguous.

In the United States, white chocolate is defined under 21 CFR §163.124 of the FDA. To be labeled and sold as white chocolate, a product must contain:

≥20% cocoa butter by weight

≥14% total milk solids

≥3.5% milk fat

No cocoa solids

No fats other than cocoa butter

Any product using vegetable fats in place of cocoa butter cannot be labeled "white chocolate." Those products fall under “compound coatings” or confectionery.

In the European Union, Directive 2000/36/EC defines white chocolate as a product containing:

≥20% cocoa butter

≥14% milk solids (including ≥3.5% milk fat)

No cocoa solids

The EU does permit the use of cocoa butter equivalents (CBEs)—non-lauric fats such as shea stearin—up to a maximum of 5%, but only if the product still contains the minimum required cocoa butter and only with mandatory labeling (“contains vegetable fats in addition to cocoa butter”).

CBEs are not substitutes. They are legally tolerated additions, not replacements.

Codex Alimentarius (CODEX STAN 87-1981) mirrors these definitions closely, and non-cocoa vegetable fats are permitted only where explicitly allowed by national law and disclosed.

Across all three systems, the logic is consistent, acknowledging cocoa butter’s defining role.

The persistence of the claim “white chocolate isn’t really chocolate” cannot be explained by regulation. It survives because regulations are invoked selectively—only when they confirm conclusions already formed through taste, availability, or cultural convictions.

This debate is not about definitions but about shallow narratives.

Preference is not a standard.

This pattern extends beyond white chocolate. Much contemporary food discourse is driven by preference-based authority, where:

Likes and dislikes are framed as evaluations.

Exposure is conflated with understanding.

Consumption is mistaken for tasting.

In chocolate, this appears in the casual use of mass-market flavor descriptors such as “bittersweet” or “semi-sweet” as if they were meaningful quality indicators.

These terms originate in commercial classification systems designed to differentiate similar industrial products. They do not describe origin, genetics, fermentation, or process. When they are treated as universal benchmarks, they signal that evaluation has not moved beyond the retail shelf.

This dynamic is amplified by social media ecosystems that reward popularity over expertise.

A declaration that white chocolate is “for broken palates” performs well because it reinforces shared assumptions while flattering the audience.

Correction demands effort; affirmation does not. As a result, repetition becomes confirmation, and the absence of challenge becomes truth.

Most people think white chocolate isn’t ‘real’ because most of what they’ve tasted isn’t chocolate at all. It is supermarket confectionery.

Within the fine-flavor sector, this inconsistency is particularly revealing.

The movement emerged to challenge the idea that chocolate quality could be reduced to color, sweetness, or percentage. It insists on criteria: origin, genetics, post-harvest practices, and maker decisions.

Yet when white chocolate comes up, these principles often disappear. Products are dismissed solely based on personal taste and the absence of cocoa solids, undermining the framework the sector claims to uphold.

In this industry, preferences aren’t standards. Professionals must work with objectivity.

I don’t even prefer white chocolate, and that’s precisely why opinions stay out, standards remain in. If we call ourselves experts and true chocolate connoisseurs, we don’t erase a category; we define it.

Understanding white chocolate does not require liking it. It requires examining how food knowledge is produced, circulated, and validated.

White chocolate is misunderstood because access and availabilty has shaped perception.

Most people did not reject it after an informed evaluation. They cast back substitutes and imitations, mistaking accessibility for truth of the matter in the chocolate world and recitation for understanding.

When judgment precedes knowledge, certainty becomes performance rather than conclusion.

What defines real white chocolate

White chocolate does not require defense as a personal preference, nor reframing as healthy or virtuous. Those strategies replicate the same logic that elevated dark chocolate through similar wrong narratives.

What white chocolate requires is accuracy: the same insistence on ingredient integrity, process transparency, and evaluative discipline that the fine-flavor world claims as its foundation.

What defines real white chocolate is not the color - white vs dark brown - but the cocoa butter directly extracted from cacao beans.

Fat, sweetness, and the confusion between taste and standards

One of the most persistent misconceptions about white chocolate is the claim that it is “just fat and sugar.”

This assertion collapses under even minimal technical scrutiny.

Cocoa butter is not a generic fat. Nearly 90% of its structure is defined by three triglycerides—POP, POS, and SOS—whose specific ratios govern crystallization, snap, and the formation of the stable β-V polymorph. This crystalline structure is responsible for chocolate’s narrow melting range near body temperature and flavor release during consumption.

Even small deviations in triglyceride ratios measurably alter melting behavior, crystal size, and polymorphic stability. This is why cocoa butter equivalents must closely match cocoa butter’s molecular profile, and why lauric fats used in substitutes produce waxy textures, greasy mouthfeel, and distorted aroma release (unpleasant taste).

What many people identify as “waxy” or “greasy” is most likely not "made of cocoa butter". It is the sensory footprint of foreign fats used in low-grade confectionery and in compound coatings. These products dominate baking aisles because they are engineered for heat stability and cost, not as the ultimate expression of taste. Yet, they are routinely treated as representative of white chocolate itself.

The same reductionist logic is applied to sweetness.

White chocolate is often dismissed as inherently too sweet, as if sweetness were a natural property rather than a formulation decision. In industrial products, sugar compensates for aromas stripped away by deodorization and low-quality sourcing. When cocoa butter contributes no aromatic complexity, sweetness becomes the primary incentive.

This outcome is not intrinsic to white chocolate. It is the result of upstream decisions—exactly as excessive bitterness and burnt taste in mass-market dark chocolate result from aggressive roasting, alkalized cocoa powders, and poor sourcing (commodity cacao).

Fat itself is not the problem; confusion is.

Cocoa butter is routinely reduced to a generic “bad fat,” but this assumption has no scientific basis.

In reality, cocoa butter is composed primarily of stearic, palmitic, and oleic acids. It contains no cholesterol, has a higher smoke point than dairy butter, and stearic acid—the dominant saturated fatty acid—is largely converted into oleic acid during metabolism, the same monounsaturated fat dominant in olive oil.

These characteristics do not elevate white chocolate's nutritional value, nor do they need to. They simply show that treating cocoa butter as an inherently "unhealthy" is chemically inaccurate and analytically shallow.

Food evaluation in gastronomy has never been based solely on nutrition. Technique, ingredients, flavor combinations, novelty, and tasting experience are treated as legitimate dimensions of quality. Foods rich in fat, like foie gras, are routinely judged as a delicacy by chefs and foodies rather than on moralized nutritional criteria. White chocolate belongs to this category of gourmet desserts.

By rejecting white chocolate on the basis of fat and sugar content, the discussion slips into dietary preference.

Disliking white chocolate is always valid. Declaring it illegitimate on the basis of that dislike is not. Standards are collective; taste is personal. When the two are conflated, evaluation collapses into consumer reaction.

The confusion deepens when eating is mistaken for tasting.

Tasting requires an analytical distinction between pleasure (a matter of personal preference) and assessment. Claims of having “tried white chocolate at every level” lose meaning when reference points remain industrial, and vocabulary remains retail-driven (too sweet, semi-sweet, bittersweet, bitter, etc.)

Groundless common sense based on conventional wisdom does not reflect the truth of the matter. Self education do. In nutrition and food culture, most knowledge is acquired independently. Information is accessible. What is often missing is not access, but the willingness to question familiar assumptions, to verify what sounds convincing, and to confirm claims rather than adopt the tales that circulate most easily.

The missing question: cocoa butter choice

The most telling omission in the white chocolate debate is the sourcing of cocoa butter.

While fine-flavor chocolate emphasizes cacao origin, cocoa butter is often treated as an afterthought, used indifferently. Additionally, many chocolatiers rely on deodorized commodity cocoa butter without questioning origin or sensory impact at all.

When the resulting white chocolate products taste neutral, the limitation is attributed to the category rather than the ingredient choice.

A rare counterexample

There is, however, a shift.

Some chocolate makers have begun pressing cocoa butter in-house from fine-flavor cacao, avoiding deodorization. Their choice demonstrates that cocoa butter can carry origin-linked aromatic signatures even without cocoa solids.

This step in the chocolate-making process is demanding, difficult to scale, and unforgiving of shortcuts:

Sugar levels cannot conceal poor ingredient quality.

Artificial vanilla is immediately apparent.

Milk powder selection matters.

Deodorization choices carry immediate sensory consequences.

Truthfully:

White chocolate made with natural single-origin cocoa butter is the rarest chocolate in the world. If you cannot press your own cocoa butter in-house, it is pretty challenging to find natural single-origin cocoa butter at the distribution level.

Why availability distorts judgment

This difficulty challenges the idea that white chocolate persists only because it is profitable.

If that were true, supermarket shelves would be full of it.

They are not.

Milk chocolate dominates because they align with mass-market economics and familiarity. White chocolate barely exists outside baking supplies, which reinforces the misconception that the compromised version defines the category.

The exact mechanism is known for dark chocolate.

Most dark chocolate available to consumers is poorly sourced (commodity or bulk cacao farmed with a high carbon footprint), ultra-processed in big chocolate factories, heavily roasted, and stripped of aromatic complexity.

EXTRA DARK BROWN becomes a visual proxy for quality, wellness, and "cacao content", even when the product is stripped of any benefits with an unedible taste.

My relationship with chocolate began here: I always loved dark chocolate. I didn’t love what was available. I went looking for better chocolate. That’s how I discovered the bean-to-bar world.

Dispel the wrong conclusion

The claim that white chocolate is “not real chocolate” rests on a single assumption: that cocoa solids are the defining and decisive criterion for legitimacy.

If that were true, it would require consistency.

Across jurisdictions, chocolate is defined by composition, not by color, bitterness, or perceived nutritional virtue.

White chocolate is legally defined by cocoa butter and milk solids. Dark chocolate is defined by its cocoa mass content. Both cocoa butter and cacao mass are extracted from the same cacao bean. Their separation is the result of processing, not of deception. The absence of cocoa solids defines a category; it does not invalidate it!

The problem arises when cocoa solids are treated as a shortcut to nutrition, quality, and authenticity.

In commercial chocolate, the cacao percentage printed on the packaging does not reflect cacao solids alone. Many consumers interpret it as a direct measure of non-fat cacao solids and therefore a proxy for optimal choice. In reality, these percentages reflect combinations of chocolate liquor and cocoa butter.

The irony becomes unavoidable:

People reject white chocolate because it lacks cocoa solids.

Yet the dark options, most widely consumed, contain much less cocoa solids than the label implies while relying on bitterness, dark color, and alkalized cocoa powder to reinforce the impression of “high cacao.”

As a result, the nutritional assumptions consumers make about “70%”, “80%”, “90%”, and “99%” products are always inaccurate. And, the firm belief "white chocolate is not real chocolate" survives because it is built on a false premise.

Only dark chocolate made exclusively from "cocoa mass and sugar" offers percentages that exactly correspond to "cacao solids content." These bars exist, but they are rare and solely confined to the craft and bean-to-bar niche.

Over the years, I have tasted and reviewed several of them. You can check my "Review" page or jump straight to my favorite tasting experiences:

White chocolate is not the lucrative center of the industry. Dark and milk chocolate are. They are the categories that dominate shelves, advertising, and health narratives. They are also the categories most protected by consumer misunderstanding and marketing simplifications.

The result is a curious inversion: white chocolate is accused of illegitimacy, while the most commercially profitable products are allowed to trade on visual cues, percentages, and nutritional myths without scrutiny.

Most consumers have never tasted white chocolate made with natural, non-deodorized single-origin cocoa butter. Basically, they have barely encountered white chocolate at all outside baking products and industrial candies, which means they reject not white chocolate itself but the lack of real examples.

I am not arguing for white chocolate as a superior choice. I do not prefer it. But dismissing an entire category on theoretical grounds—while accepting far more consequential inconsistencies elsewhere—reveals that this debate is not about chocolate. It is about which folktales are easier and more convenient to sell.

The real commercial fraud isn’t white chocolate. It’s the mass-market positioning of dark that uses cocoa content percentages, color cues, and nutritional myths to signal purity they don’t actually embody.

So the question is not whether white chocolate is chocolate. The question is: why are standards enforced where they cost nothing, and ignored where they would disrupt the market?

Comments